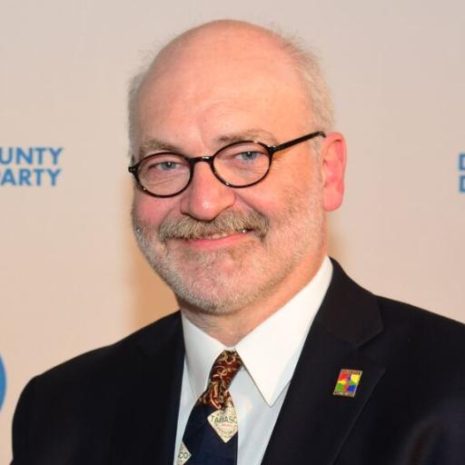

Nashville Councilman Recounts His Immigrant Past and Shows Just How Much Determination Can Make a Difference

Date: August 30, 2016

It was a fire in his house that finally convinced Fabian Bedne, now a Nashville councilman and part-owner of an architectural firm that generates up to a quarter of a million dollars in annual business, to become a U.S. citizen. Afterward, he says, “everyone in the community was so nice, supportive, and helpful. I felt a sense of gratitude that made me realize I really did want to be here.” Bedne filed his immigration paperwork in Tennessee’s 5th congressional district, where he resides. When his check was cashed, he took it as a sign that his documents were being reviewed.

Then, nearly an entire year went by. “I hadn’t heard a thing,” he says, “but I left it alone. Being from Argentina, you don’t want to rock the boat with the government.” When Bedne finally did inquire about his status, he was dismayed to learn that his application hadn’t been processed due to his check being $25 short. “In all that time, no one ever reached out and told me,” he says, his frustration still palpable. “That experience is what ultimately informed my efforts to help others who are navigating the process, because I know how bureaucratic the process can be.”

What would make me feel better is if our [immigration] system were more efficient, easier, and inclusive.

Helping others has been Bedne’s focus since he first migrated from Buenos Aires in 1990. An architect in his home country, Bedne moved first to Columbus, Ohio, to restore and repurpose abandoned homes as affordable housing. The work helped to boost the local economy by training and then hiring residents at a nearby homeless shelter. The crew he put together met his labor needs and set up roughly 75 people for future jobs. The whole thing was such a success that the one-year program turned into five years. Bedne was asked to stay, but while he sorted out his visa situation, his employers were required to advertise the job. He had no reason to worry though. “I was an immigrant-architect doing a job that no Americans wanted to do—no one applied!”

Next, Bedne and his family moved to Nashville for an architecture job, but he lost it during the Recession, in part because when he first moved to Tennessee, it wasn’t possible for architects with foreign degrees to apply for licensing there. Though the laws have changed since then, Bedne says it is the oft-changing requirements that have prevented him from being able to complete the certification process so far. Undeterred, he partnered with three other immigrants to open a small architecture and residential design business aimed at Latino-owned properties. “We just did a Latina church that was in the millions of dollars,” he says. “We recycled an old supermarket that had been sitting empty for many years. Now it’s a church with 5,000 seats, which brings people together and created all these jobs.”

In 2011, he became Nashville’s first Latino elected official. As a councilman, he’s become a point of reference on matters of immigration for many of the city’s residents. “I remember someone once asking me if I didn’t feel bad that I did everything by the book while there are people coming here without papers and still managing to get by,” he recalls. “And I said, ‘Well, if I had cancer, I don’t wish it on other people.’ So me having to deal with a cumbersome system? That doesn’t make me want for everyone else to also have to deal with it. I never feel bad for undocumented immigrants being here. I feel bad that our messed-up system makes it so they don’t have a way to apply for a visa or have an opportunity to get adequate housing. And what would make me feel better is if our system were more efficient, easier, and inclusive.’”

Bedne is certainly doing his part to make that happen. “As an immigrant, I’m passionate about things that other officials wouldn’t necessarily care or know about,” he says. For him, that means fighting for issues like affordable housing for the city’s Hispanic population and increasing workplace diversity. Rather than accept the “lack-of-qualified-people” reasoning he was given to explain the dismal number of Latinos working in public management positions around the city, Bedne did some digging. It turned out that many immigrants were qualified for those management positions that didn’t require special licensing, having studied and worked in these fields back home. But they lacked the funds and the time to go back to school in America to qualify for the management positions that did require licensing. Bedne suggested that applicants be judged based on their experience and education abroad, and not necessarily by their U.S. diplomas, or lack thereof. At first, his suggestion was met with skepticism, but eventually Bedne secured approval from the city council, and a statement encouraging candidates with accredited foreign degrees to apply was added to every city job description in Nashville.

But Bedne doesn’t only work on behalf of Nashville’s immigrants. Earlier this year, when a big gas company sought to run a pipeline though the city, Bedne publicly opposed it after residents in his district voiced their disapproval. “One of the things that attracted me to the United States was that people have the right to decide what happens in their communities,” he says. “So I put together legislation that, through zoning, will give local communities the power to decide if a gas compressor station can be built there.” The bill passed in Nashville and will advance to the state level for review.

If you’re thinking that you may get deported, instead of continuing to spend your money on cars and houses, you’re going to put it in a safe place because you may be gone tomorrow. It [is] really bad for the economy.

In the end, Bedne wants to push for change that helps the economy, and this often means supporting immigrants’ rights. He remembers when the state’s undocumented immigrants were allowed to apply for driver’s licenses. At that time, the undocumented population felt “safe and engaged” in Nashville. “There was so much money going around. It was really great for the economy.” But after the policy was overturned in 2006, many immigrants began to flee the state. “The economy that was flourishing and doing so well was just stripped,” he says. “Businesses, big grocery stories—they all started closing. If you’re thinking that you may get deported, instead of continuing to spend your money on cars and houses, you’re going to put it in a safe place because you may be gone tomorrow. It was really bad for the economy.”

Although Bedne thinks Nashville has historically been welcoming of immigrants, he knows that reforming the current system is key to helping the city’s foreign-born population fully integrate into their communities. “People here tend to complain about things like overcrowding because a lot of Latinos often live in one house,” he says. “Yes, that violates Nashville’s [housing] code, but what are immigrants supposed to do? Our policies make it extremely difficult for them to buy houses for their families. If we have reform, many of the problems people complain about would go away. Helping immigrants improves everyone’s quality of life.”