Without Immigrant Doctors, This Small Town Would Have Almost No Access to Physicians

Date: July 6, 2016

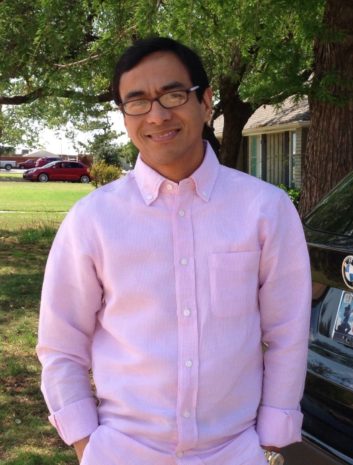

It’s a rare day that Dr. Emmanuel Barias isn’t asked medical questions when he’s out and about town. “Dr. Manny!” is a constant refrain, the melody that accompanies his life in his adopted Oklahoma town. While eating at a cafe, a woman tells him she’s lost weight and asks about her diabetes medication. While shopping at Walmart, another lifts her shirt and asks him to inspect a rash. While relaxing at home, his front doorbell rings often. He always answers. “That’s the dynamic here, and I like it,” Barias says. “I don’t want to discourage it, as long as they’re OK with their privacy.”

Barias is one of eight physicians practicing in Guymon, a town of 12,000 people on the high plains of the Oklahoma panhandle that supplies workers to the area’s cattle feedlots and pork plants. Seven of the eight doctors are from the Philippines, recruited to America to help ease a physician shortage in medically underserved areas.

I love that we are welcome here. I love that people from other countries are looking for work here. It works in rural America.

All seven made their way to Guymon by way of the Conrad 30 Waiver Program, which allows foreign doctors who have trained in the United States to stay in the country after their residency programs if they agree to practice in a medically underserved area for three years.

Like many predominantly rural states, Oklahoma faces an acute physician shortage that’s predicted to grow worse as the population ages. The state had 216.5 practicing physicians per 100,000 people in 2014, the 47th lowest ratio in the country. In Texas County, Barias and his fellow immigrant doctors bring the ratio to a meager 32 physicians for every 100,000 residents.

What would the people of Guymon do without the Conrad 30 Waiver? Barias is afraid to hazard a guess. The closest large town is Amarillo, Texas, a two-hour drive. “It’s extremely difficult to recruit physicians here,” Barias says.

When Barias graduated from the University of Philippines College of Medicine in 1995, he says that most of his classmates immediately accepted higher-paying positions abroad. Barias moved to the southern Philippines, where he served in a poor, remote region. “I chose to stay because of my government scholarship to medical school,” he says. “I thought at that time I would give back.”

By 1998, however, Islamic militants had made the region dangerous, and Barias finally accepted an offer to do a residency program in the United States. Former classmates who’d already moved to America paid his $1,500 licensure exam fee, and he decided to focus on family medicine. He was fulfilling his Conrad 30 Waiver duties in Grand Rapids, Michigan, when two of his medical fraternity brothers from the Philippines invited him to join their clinic in Guymon.

“Let’s try rural,” he said to his wife. “Let’s try it for a couple years.”

They’re now finishing their eighth year. In addition to working at the clinic and hospital, Barias opened a medical spa, and he and his wife opened two coffee shops, a gift and flower shop, and a restaurant – businesses that combined employ 60 people. Their cuisine consistently wins Certified Healthy Awards from the state, a point of pride for the doctor. The couple is now considering retiring in Guymon.

“People tell me at the clinic, ‘Hey, Doc, I really appreciate what you’re doing,’” he says. “I love that we are welcome here. I love that people from other countries are looking for work here. It works in rural America.”